Update: I won! Thank you to everyone who voted. Rocks In His Socks came in first and will be published in Bookkus’s short story anthology in early 2013.

Page 7 of 8

I read a great post on Rachelle Gardner’s blog by Aimee L. Salter about indie authors versus the traditionally published. Actually it is essentially about writers versus other writers, but it got me thinking.

Recently, two big things happened for me in the publishing industry: the first, as you may know, was that I signed with an agent who has just sent my first book out to publishers for consideration. The second is that I started up an indie publishing imprint, called Tenebris Books, under Holland House Books.

Aimee’s post reminded me of something I’ve thought about a few times since these events occurred – I’m playing both sides of the fence. Although I agree with Aimee in that I don’t think there should be such a divide between indie published-authors and traditionally published authors, I wonder whether those who see the divide as an Us vs Them situation would think my decision to start this imprint is somewhat hypocritical. After all, the authors I hope to publish would be on the opposite side of the writing fence to me, as I currently seek a legacy publisher for my own work.

However, I don’t think any author who seeks or has a traditional publishing contract has any right to put themselves above an indie published author. The choice to go independent is no longer a sign of a writer who has given up and is now slumming it. There are many legitimate reasons why someone might go independent, not least because they hope to make a career and a living out of writing, and independent royalties are often much higher than traditional ones. It might also be for for more individual attention from their editor, or for more say in content, cover art, marketing strategy or any number of decisions often taken out of the writer’s hands by a legacy publisher. And it’s a mistake to assume that independent publishers take on any old manuscript thrown their way; I know of books which have been rejected by independent publishers only to go on to success with agents and traditional publishers.

For my own part, what I am looking for with my imprint is something that may not find a home with a mainstream publishing house, and I may have the opportunity to give a home to books that might not find a place anywhere else. That doesn’t mean I’m planning to fill my catalogue with rejects, it means I’m seeking something that is not so much outside the box, but more that it has little bits of paper in many different boxes. I researched long and hard to see if I could find a name for what I’m looking for, and the closest thing I found was Weird Fiction, which hasn’t existed as an acknowledged literary genre since early last century. And why do I want this? Because I want to read it, and know others who do, too. All those people who watch and love films like Pan’s Labyrinth, Coraline, The Others, The Orphanage and love classic folk and fairy tales, they read books too, they just might not know where to find them. I want to help.

On the other side of the literary fence, which is simply a different shade of green, I’m hoping to land a publishing contract that will send my book(s) on a journey around the world. I’m starting out in the US, but Amaranth is actually not set in any specific country; the entire Eidolon Cycle is set in the fictitious city of Lennox, which could be anywhere that has big cities, a coastline, and where it snows in winter. I wanted to write something that any reader could feel close to, like it might be happening right where they live, or somewhere they once visited. Like Springfield on The Simpsons, only on an international scale. Part of why I wanted a traditional publisher is the international reach; they can get my book into hands that might not have found it without them. I won’t pretend there isn’t a little bit of validation involved, if I’m honest, but really the best and most important validation comes when people are reading and enjoying what you’ve written, no matter who got the book from writer to shelf.

I am very pleased and excited to announce that Amaranth and I are now represented by Michelle Johnson of The Corvisiero Agency. Michelle is a published author, professional editor and is now working under Marisa Corvisiero who launched her own agency earlier this year. They’re a great team and I’m really looking forward to working with them.

The next part of the journey is likely to be slow and, at times, painful, but I’ve been so motivated by Michelle’s enthusiasm for and confidence in Amaranth’s potential, that I’m feeling positive about the road ahead. Of course it helps that I’m busy working on the next book in the series, Sweet Alyssum, and have mapped out the plot for the third and final book, Bella Donna.

As we progress, I will post news and developments here and on my Facebook Page.

For those authors who are on the hunt for an agent, you have my sympathy and good wishes; it’s not an easy process and there were times I almost gave up. Indeed, I had a plan to publish under a small, indie imprint by the end of the year if I found no success in the big leagues. However, persistence pays (as well as having a strong product to sell and a very strong query letter). By the time I signed with Michelle, I had submitted over 50 queries in both the UK and United States and received something like four requests for the full or partial manuscript.

It’s a tough time in the industry and you do need to have a thick skin to get through the process unscathed. I read that something like 3% of all queried books are taken up by agents, and still only half or less than those go on to get a publishing contract, then of that tiny percentage, many will sell less than 100 copies. Sobering statistics for the aspiring author. But, as most writers will tell you, very few people are in this line of work for money. Most of us do it for the joy of writing – and I’m definitely one of those.

Talking to writer friends online about a year ago, I realised how much I was missing being able to talk to other writers face-to-face. When I met Brian, a fellow writer and Oslo resident on a writers’ website, I got to thinking how great it would be to have a local network, especially of international writers. So I decided to start the Oslo International Writers’ Group. It began as a Facebook group, but a few of us quickly agreed to have regular meetings to talk about writing and critique each other’s work.

We’ve now been meeting regularly for more than six months, each month focusing on one writer’s submitted piece, which has been of great value both to the writer and the critics. We’ve read some great work so far, as well as talked about our own work and experiences in relation to the discussed pieces.

Now we’re venturing into new territory by putting together an anthology of short stories, both fiction and non-fiction, with the theme “Adaptation”. The theme will be interpreted by each individual writer in their own way, and each story will be written to showcase the writer’s personal style.

Many of us are ex-pats, so the theme of Adaptation is close to our hearts. First drafts will be presented and discussed at our next meeting after the summer break, and I’m really looking forward to reading what each of our talented members comes up with.

Watch this space for more details and news of a release date!

The Oslo International Writers’ Group is open to any writer living in or around Oslo, Norway. You are welcome to join the Facebook group without attending the meetings – join here. We exist to discuss writing generally as well as our individual writing projects, to support and promote each other and to add a social element to the oftentimes lonely life of a professional (or amateur) writer.

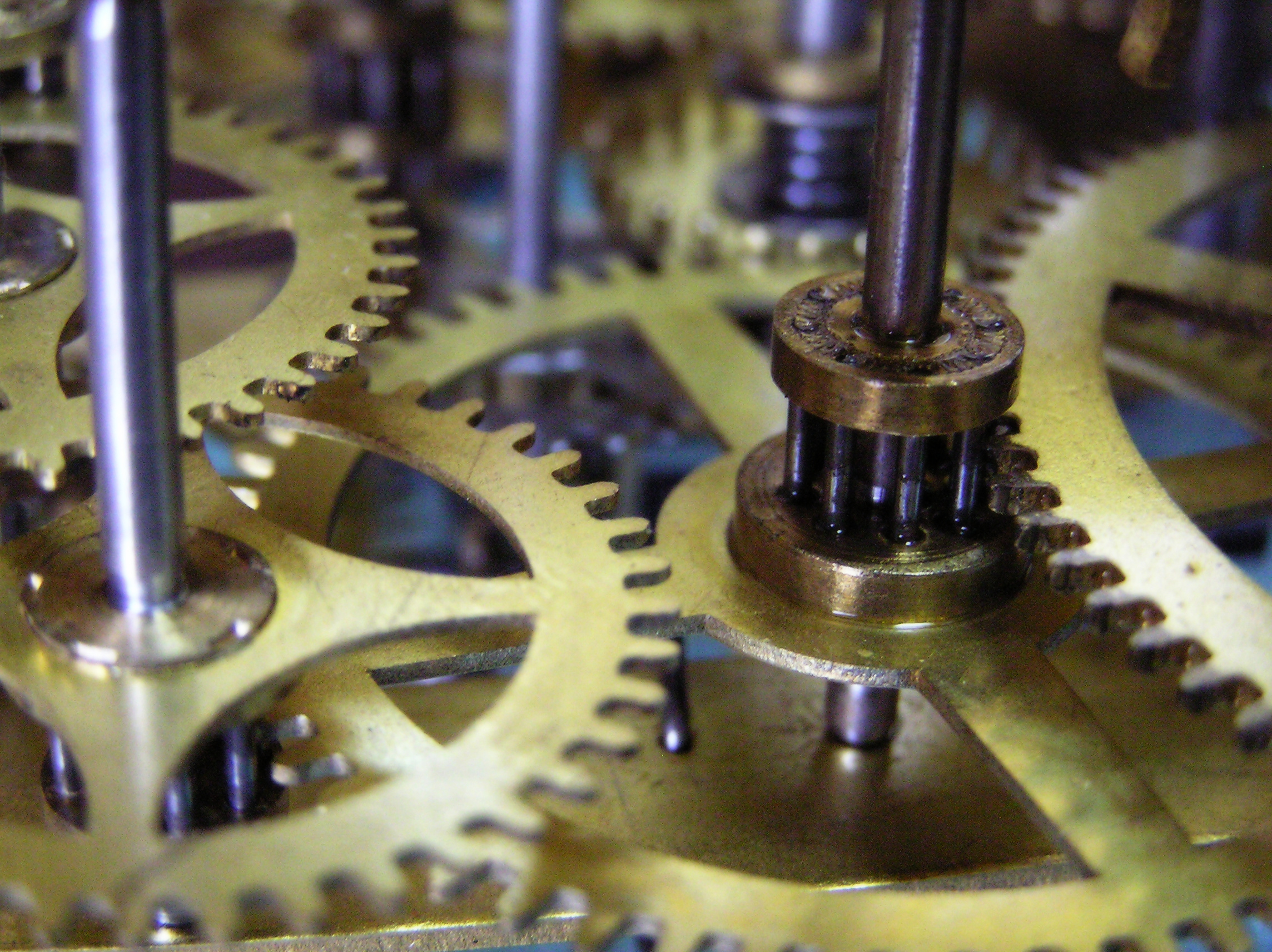

A brand new publishing imprint, Kristell Ink, recently approached me to write a short story for their upcoming Steampunk anthology called Scriptorian Tales. I’m delighted to be a part of this project, even though this is a step into new territory for me, genre-wise. Steampunk is a fascinating genre, blending historical fiction with the science that might have been. It’s not for the faint-hearted and there is quite a bit of research to be done to make the stories authentic. Nevertheless, I am excited about my idea and am well into writing my first draft.

Here’s the brief from Kristell Ink:

The loopers, agents employed by the quorum on Tellus Primus, travel to parallel worlds to gather intelligence and weapons for the impending Chromerican invasion.

Tellus, Gaia, Earth, they all seem the same; until one day, Looper Team C from the Beta site (the colonies of British occupied America) land on a planet they name Earth 267 – where technology has taken a slightly different turn. Giant steam-powered machines (airships, scuttle-creatures, hot air balloons) all work diligently alongside the traditionally fossil-fuelled contraptions (cars, lorries, trucks), and society remains firmly in the grasp of Victorian ideals and etiquette.

During the loopers’ undercover search of what they come to realise is London, they stumble upon a locked room, full of the weird, the wonderful and the frankly insane. Inside that room lays a huge book bound in some unknown material.

Inside that book are the strange tales recorded by the Scriptorians, who created the Great Library of London that was tragically lost in some long ago fire.

The Scriptorians were elite explorers, scientists and chroniclers, chosen for their wordsmith abilities, their tenacious belief in uncovering the truth, their passion for the bizarre and baffling. There is some evidence that these mysterious adventurers, fighters and writers also discovered the technology to loop and visit other parallel worlds.

These are those tales…

I will take on the role of honorary Scriptorian, and will pen one such tale. I’m very excited to be part of it, and can’t wait to read the stories that will feature alongside my own. I’ll post again when my draft is complete (it’s due by the end of August) and tell you more then.

As long as there has been literature, there has been a desire and need to group it into categories. There is no officially agreed set of literary genres, and the more I become involved in the publishing industry, the more I realise that these days genre is as much about target audience and marketing strategy as it is about stylistic categorisation or plot type.

It seems that many publishing houses and literary agents are increasingly focused on categorising books by what they believe a given demographic will buy and read, rather than the contents of the books themselves. This makes it incredibly difficult for writers whose work crosses age, gender or racial boundaries and has potential appeal to a wider audience. You’d think wider appeal would mean a more saleable book, right? Not according to the experts.

Let’s take the genre currently known as Young Adult, for example. (Note: to me this has always been a ridiculous name for the age-group spanning the years between 12 and 18: since when is a twelve-year-old ANY kind of adult? But that’s a rant for another day.) The basic requirement for a Young Adult novel is that its protagonist is between the ages of 12 and 18 years (though 13 to 17 seems to be the best bet), and deals with the sorts of issues kids in this age range are interested in and go through themselves (or, if we’re going to be totally cynical, what older people think kids in this age range are interested in). While I believe there’s a very appropriate safety-net involved in this categorisation, (you can at least be fairly confident they’re not going to contain a lot of gratuitous sex, swearing or violence), to suggest that all people this age like the same kind of books is ludicrous. Do all people between 30 and 50 like the same books? So then a sub-genre system is employed; we have YA Contemporary, YA Fantasy, YA Sci Fi… and so on.

So what’s wrong with that? you ask. Nothing. Except that it pigeonholes both the books and the people who might read them. If you categorise books by life-stage, you’re saying that once you’ve completed a life-stage, you no longer have any interest in it, even for nostalgia’s sake. Or if you haven’t reached a certain life-stage, you can’t be interested in it yet.

Have you ever felt embarrassed because you enjoyed a Young Adult title, even though you’re in your twenties, thirties or older? I know plenty of people who were embarrassed to admit they’d read and loved The Hunger Games trilogy simply because it was classified YA. And yet, had the protagonist been just a couple of years older, it would have been marketed as Adult Dystopian, and those people would have been able to proudly proclaim how much they enjoyed it.

Then there is the lost genre, dubbed ‘New Adult’ by St. Martin’s Press in 2011. A ‘New Adult’ is someone in the approximate age range of 18-25, dealing with the pressures of becoming responsible for his or her own life for the first time. It’s a period in anyone’s life fraught with change, stress, excitement, adventure… all the ingredients for a great story. And yet, this genre is a black-hole according to a vast number of agents and publishers. Why? Because apparently 18-25 year olds don’t read.

Things became interesting this week when I received not one, but two requests from New York literary agencies who want to read more of Amaranth. It’s both exciting and terrifying to come so close: it could be the start of something huge, or it could just give me further to fall. But what I want to be able to take away from this development is the knowledge that there are at least two agents out there who think my work is worth their time. That is HUGE.

What does it really take to be a writer? Talent? Skill? What happens when everything else gets in the way and a writer can’t find time to write? After all, we have day jobs, bills to pay, children, partners and pets to love, friendships to maintain… everything takes up time, and it can begin to feel like things are attacking the time that could be spent writing. This is something I talk about in my guest blog on Bookkus.com.

As part of their blog series entitled “The (Vacant) Author”, my post, The Militant Author, explores what it’s like to fit writing in around life, and life in around writing.

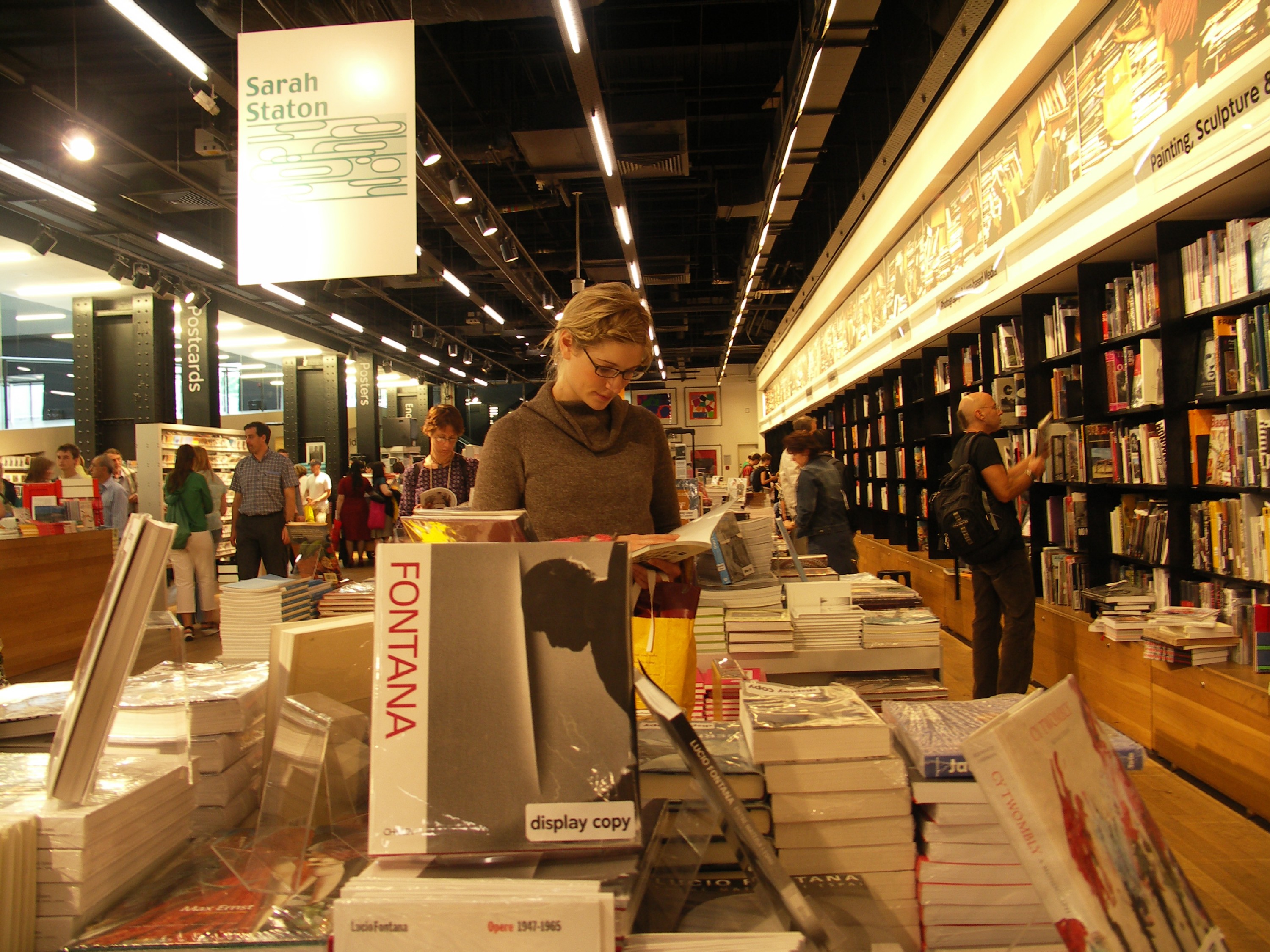

Bookkus is a new, independent publishing house looking to enlist real people to choose the books they publish. They’re currently taking on submissions from authors as well as looking for readers who want to participate in getting the books they are passionate about published.

I recently got in touch with Rochelle Stone of Barefoot Basics, an Australian-based marketing company working to assist authors entering the publishing industry for the first time. She requested an interview about my novel, Amaranth, which has today been published on the Barefoot Basics website. I talked to Rochelle about the book itself as well as how I manage my time between writing, self-promotion and holding down a day job.

My current work in progress is proving quite a challenge, and one of the key reasons for this is voice. When I mentioned my struggles to a friend recently, he said he could always recognise my voice in my writing, and that when he reads my work, he hears my voice in his head. I tried to explain this wasn’t quite what I meant, but I realised he had a point. I began to wonder if it is actually possible to separate the writer from the writing.

Amaranth is written in the first person, and the narrator is a nineteen year old girl named Eva. If I’m honest with myself, Eva’s narrative voice is very close to my own internal narrative; I wrote her much the same way I would write myself. She has a dry, dark sense of humour, is given to pessimism (and melodrama) and can be quite caustic. It was quite easy to write from her perspective.

However, the next book in the series is written from a different character’s perspective, and though she is also a girl in her late teens, she is a very different character to Eva. She’s bright, bubbly, mischievous and though she has a dark past, she refuses to let it get her down. It was a complete shift in gears for me, and I’m glad I took the time to write some short stories in between novels so that I could cleanse my palate of Eva, as much as is possible anyway, given the points I made above.

The interesting part is that two chapters in, though I’m struggling to keep the new voice authentic through word choice and structure, I’m finding the best thing I can do is to adopt her mindset. Method writing, perhaps? In order to know instinctively how she would react and what she would say in any given situation, I need to think like she would. I’ve found it rather therapeutic to shift my brain into nothing-gets-me-down girl; I’ve stopped for a break a number of times and found that I’ve been unconsciously smiling.

Reading back through the chapters I’ve written so far, I have managed to create a distinctly different voice for this novel, and yet my writing voice is still in there. Perhaps there are writers in the world who are true chameleons and can write in a completely different voice from book to book, but I am not quite there yet. And yet… I’m not sure I want to be. Not entirely. When I pick up a book by a favourite author, I want to hear his or her voice in there somewhere. It’s like a trademark. No, on second thoughts, it’s more subtle than that. It’s more of a watermark. Something at the nucleus of the writing that stamps it as theirs, and without it, I wouldn’t be able to trust the unfamiliar book to deliver what I liked about previous works.

Ideally, I want to find a balance. I hope that at some point my work will have fans who don’t know me personally, and don’t know what my real-life voice sounds like. For those people, I would hope to create something new and engaging each time, but with an intangible familiarity that allows them to trust that they’re going to get a healthy dose of what I do, no matter who the characters are, what they achieve or where I take them.